The Paradox of Knowing Better

You know exercise would help. You’ve read the articles, heard the recommendations, maybe even experienced those rare moments when physical activity made everything feel clearer and more manageable. Yet here you are again, choosing the couch over the gym, scrolling instead of stretching, planning a workout routine you know you won’t follow.

If you have ADHD, this isn’t about laziness or lack of willpower. It’s about ADHD exercise motivation—or more precisely, how your brain’s unique wiring affects your ability to initiate and sustain movement. Understanding why ADHD exercise motivation is so challenging requires looking at executive dysfunction, dopamine regulation, and the invisible barriers your brain faces daily.

Why Exercise Matters for ADHD Brains

The benefits of exercise for ADHD aren’t just theoretical. Research consistently shows that physical activity triggers the release of dopamine and norepinephrine, the same neurotransmitters that ADHD medications target. A single session of moderate aerobic exercise can improve attention, boost motivation, and enhance executive function for one to two hours afterward.

Regular physical activity offers even more substantial benefits: improved executive functioning, better emotional regulation, reduced hyperactivity and impulsivity, enhanced mood and reduced anxiety, and better sleep quality. Studies suggest that consistent exercise can be as effective as low-dose stimulant medication for some individuals.

Yet knowing these benefits doesn’t make lacing up your sneakers any easier. Understanding why requires looking at the specific barriers ADHD creates.

The Executive Function Wall

Executive dysfunction sits at the heart of many exercise barriers for people with ADHD. These are the brain’s management functions—planning, organizing, initiating tasks, sustaining attention, and managing time.

Task Initiation: The Invisible Barrier

Task initiation is often the hardest part. Your ADHD brain operates on what researchers call an “interest-based nervous system” rather than an importance-based one. Exercise, especially when it’s boring or repetitive, doesn’t trigger the dopamine surge needed to overcome inertia. The activation energy required to begin feels impossibly high, even when you genuinely want to move.

One study participant described it perfectly: “I can plan the perfect workout routine, have my gym bag ready by the door, and still somehow end up on the couch wondering what happened.”

Time Management and Planning

Time agnosia—difficulty sensing the passage of time—creates additional challenges. You might underestimate how long it takes to get to the gym, overestimate how much time you have available, or lose track of time entirely while doing something more stimulating. Exercise appointments seem to evaporate from your schedule.

Planning a workout routine involves dozens of micro-decisions: What type of exercise? When? Where? What equipment? For how long? Each decision drains executive resources, making the whole endeavor feel overwhelming before you even begin.

Sustained Attention

Maintaining focus during exercise poses its own challenge. Traditional workouts—running on a treadmill, lifting weights with rest periods, following a yoga sequence—require sustained attention that ADHD brains struggle to maintain. The monotony becomes unbearable. Your mind wanders. You get bored and quit.

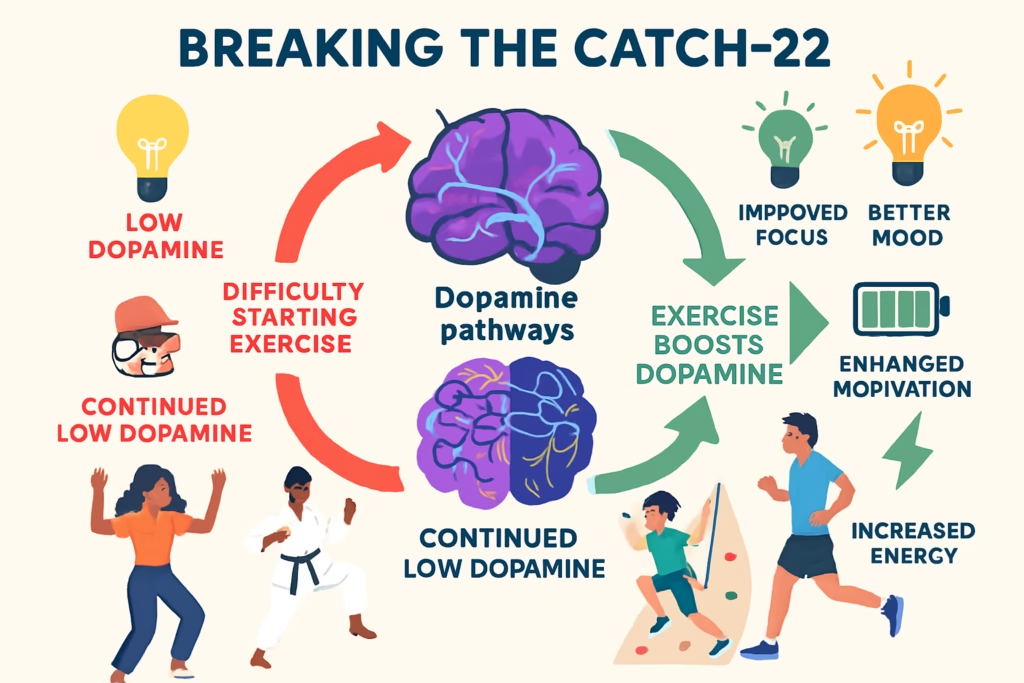

The ADHD Exercise Motivation Paradox

Dopamine dysregulation in ADHD creates what seems like a cruel paradox. Exercise boosts dopamine, which improves motivation and attention. But you need motivation and attention to start exercising in the first place. This is the core challenge of ADHD exercise motivation.

Research shows that individuals with ADHD have lower dopamine receptor and transporter availability in the brain’s reward pathways. This translates to problems engaging in activities that aren’t inherently interesting or immediately rewarding. Exercise, particularly when you’re just starting out and haven’t experienced the benefits, often falls into this category.

As one researcher explained, the ADHD brain requires stronger incentives to modify behavior than neurotypical brains. The long-term health benefits—lower blood pressure in twenty years, reduced disease risk—simply don’t compete with the immediate reward of checking social media or playing a video game. Understanding this helps explain why ADHD exercise motivation operates so differently from neurotypical exercise motivation.

Emotional and Social Barriers

Beyond executive function, several emotional and psychological factors make exercise feel impossible:

Poor Self-Esteem and Body Image

More than half of adults with ADHD in research studies identify social pressures and self-consciousness about body image as significant barriers to physical activity. Years of struggling with coordination, being picked last for teams, or feeling judged in gym class create deep-seated anxiety around exercise.

“Not knowing gym equipment very well, but wanting to learn, but being too scared to try learning on my own, where there could be other people watching me or judging me,” one participant shared. This fear of embarrassment keeps many people with ADHD away from gyms and group fitness classes entirely.

Performance Anxiety

Many individuals with ADHD report difficulty with motor coordination and multi-step movements. Traditional sports and structured exercise programs often emphasize these exact skills, creating a setup for failure and frustration.

Emotional Dysregulation

Exercise can initially feel uncomfortable—increased heart rate, breathlessness, muscle fatigue. For those who struggle with emotional regulation, these sensations might be misinterpreted as distress, triggering avoidance rather than persistence.

Environmental and Practical Obstacles

Physical and environmental barriers add another layer of difficulty:

- Cost: Gym memberships, equipment, and fitness classes require financial resources that may already be strained

- Access: Transportation to fitness facilities, especially without reliable executive function to plan trips

- Weather: Outdoor exercise becomes impossible on bad days, disrupting any fragile routine

- Injuries: Past injuries or chronic pain make certain activities difficult or impossible

- Pandemic effects: COVID-19 disrupted exercise routines for many, with gym closures and fear of contracting the virus creating barriers that persist

The Irony No One Talks About

Here’s the cruelest part: exercise itself could help with many of the executive function challenges that make exercise difficult to start. It’s a catch-22 that traps people in cycles of frustration and self-blame.

After exercising, many people with ADHD report a cascade of benefits. One study participant described it as “starting that first domino.” Exercise created motivation to start other tasks, improved ability to complete them, and provided energy that lasted hours afterward.

The window of enhanced executive function following exercise—typically one to two hours—represents a golden opportunity for tackling challenging tasks. But accessing this benefit requires overcoming the initial barrier of starting.

Breaking Through: Strategies to Boost ADHD Exercise Motivation

Understanding these barriers is only useful if it leads to workable solutions. The key to improving ADHD exercise motivation lies in working with your brain’s wiring, not against it. Research and lived experience point to several effective approaches for building sustainable ADHD exercise motivation:

Make It Immediately Rewarding

Since ADHD brains respond to immediate rather than delayed gratification, build instant rewards into exercise:

- Pair workouts with pleasurable activities: engaging podcasts, favorite music, audiobooks you only allow yourself during exercise

- Create a “dopamenu”—a personalized list of small rewards for completing movement (a favorite snack, 10 minutes of a video game, a social media check)

- Exercise with friends or join group activities for social reward

- Choose intrinsically enjoyable activities rather than ones you “should” do

Minimize Barriers to Starting

Reduce the activation energy required:

- Use the five-minute rule: Commit to just five minutes of movement. You can stop after that, but most people continue once they’ve started

- Break it into micro-tasks: Instead of “go to the gym,” break it down: “Put on workout clothes,” then “Walk to car,” then “Drive to gym”

- Remove decision-making: Lay out clothes the night before, pack your gym bag, choose your workout in advance

- Anchor to existing routines: Exercise immediately after another daily habit—right after morning coffee, during lunch break, before dinner

- Start ridiculously small: One push-up. A walk around the block. Tiny wins build momentum

Choose ADHD-Friendly Activities

Not all exercise is created equal for ADHD brains:

High engagement activities work better than monotonous ones:

- Martial arts (karate, taekwondo, jiujitsu) combine physical movement with mental focus and clear structure

- Dance classes or dance-based workouts provide music, novelty, and social interaction

- Rock climbing requires problem-solving and offers clear, immediate goals

- Team sports offer built-in accountability and social motivation

- Interval training or circuit workouts provide variety and frequent changes

Outdoor exercise offers additional benefits:

- Nature exposure has been shown to reduce ADHD symptoms beyond the exercise itself

- Outdoor activities provide more sensory stimulation and novelty

- Natural settings offer a calming effect that can improve focus

Short, intense bursts often work better than long sessions:

- Even 5-10 minutes of movement can boost dopamine and break through attention barriers

- High-intensity interval training (HIIT) provides novelty through constant variation

- Multiple short sessions throughout the day can be more sustainable than one long workout

Externalize ADHD Exercise Motivation and Accountability

Since internal ADHD exercise motivation is unreliable, creating external structures is essential:

- Schedule specific “exercise appointments” in your calendar with alarms

- Find an accountability partner who will show up whether you feel like it or not

- Join classes with specific times that create external structure

- Use apps with streaks and tracking to visualize progress and trigger dopamine through achievement

- Work with a trainer or coach who creates external expectations

- Post commitments publicly on social media for social accountability

Leverage Technology Wisely

Various apps and tools can support exercise habits:

- Visual timers that show time passing

- Habit-tracking apps that create satisfying streaks

- Fitness apps with immediate feedback and rewards

- Body-doubling apps or videos (working out alongside others virtually)

- Gamified fitness apps that turn exercise into a game

Reframe and Reduce Self-Judgment

The way you think about exercise matters:

- Recognize that ADHD brains work differently—this isn’t a character flaw

- Celebrate showing up, not just completing the “perfect” workout

- Give yourself permission to quit after five minutes (reducing the emotional stakes makes starting easier)

- Let go of “should”: Choose activities you actually enjoy rather than ones you think you should do

- Expect inconsistency: Your exercise routine will be messier than neurotypical people’s routines, and that’s okay

Use Stimulation to Your Advantage

Many people with ADHD find they can sustain exercise when they add stimulating elements:

- Listen to high-energy music, podcasts, or audiobooks

- Exercise while watching TV or YouTube

- Use apps that tell stories or play games while you move

- Try VR fitness games that fully immerse you

- Exercise in new environments regularly to maintain novelty

Capitalize on the Post-Exercise Window

Make the most of improved executive function after exercising:

- Pre-identify one important task to tackle in the 1-2 hours after exercise

- Schedule exercise before challenging work rather than after (when you’re depleted)

- Keep a list of tasks you’ve been avoiding to tackle during this window

- Notice the benefits explicitly—awareness reinforces the exercise habit

When Professional Support Helps

Sometimes the barriers are too high to overcome alone. Consider professional help if:

- Depression or anxiety significantly interferes with motivation

- Physical injuries require specialized guidance

- Executive dysfunction is so severe that basic planning feels impossible

- You’ve tried multiple strategies without success

Options include:

- ADHD coaching focusing specifically on exercise habits

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) to address motivation and negative thought patterns

- Physical therapy if injuries or coordination issues are barriers

- Personal trainers experienced with ADHD who can provide structure and accountability

Medication Considerations

ADHD medications can sometimes help with exercise initiation:

- Taking medication before planned exercise may provide the executive function boost needed to start

- Some people find exercising before medication in the morning allows them to maximize both the exercise benefits and medication effectiveness

- Never stop medication to “test” if exercise alone is sufficient without medical guidance

A Different Kind of Success

Success with exercise when you have ADHD looks different than the Instagram-perfect fitness journeys. It’s messier, less consistent, and more experimental.

You might exercise intensely for two weeks, then not at all for a month. You might try seven different activities before finding one that sticks. You might need different strategies in different seasons, during different life phases, or even on different days of the week.

This doesn’t represent failure. It represents an ADHD brain working with its natural patterns rather than fighting against them.

Moving Forward (Literally)

If exercise feels impossible right now, start impossibly small. Put on workout clothes. Walk to the end of your driveway. Do one jumping jack. Do it badly. Do it imperfectly. Do it while watching Netflix if that’s what it takes.

The goal isn’t to become a fitness influencer or run marathons (unless you want to). The goal is to find a sustainable way to access the cognitive and emotional benefits that movement provides—benefits your ADHD brain desperately needs.

Your brain’s wiring makes this harder. Understanding why it’s hard doesn’t make it easy, but it does make it possible to approach the challenge with compassion rather than self-criticism.

You’re not lazy. You’re not lacking willpower. You’re navigating a genuine neurological challenge that affects task initiation, motivation, and sustained attention. With the right supports, strategies, and self-compassion, movement can become part of your life—not as punishment or obligation, but as a tool that helps your brain work with you instead of against you.

The next time you find yourself planning a workout you won’t complete, remember: the point isn’t to execute the perfect plan. The point is to move, in whatever way works for you, right now. Even if “right now” means dancing to one song in your kitchen or taking a five-minute walk around the block.

Start there. That’s enough.

Key Takeaways

- Exercise provides significant benefits for ADHD symptoms by boosting dopamine and norepinephrine

- Executive dysfunction creates real barriers to initiating and maintaining exercise routines

- ADHD exercise motivation differs from neurotypical motivation due to dopamine regulation challenges

- ADHD brains require immediate rewards and high stimulation, making traditional exercise programs difficult

- Effective strategies for improving ADHD exercise motivation include minimizing barriers, choosing engaging activities, and externalizing accountability

- Success with ADHD looks different—embrace inconsistency and celebrate small wins

- Professional support can help overcome persistent ADHD exercise motivation barriers

- The goal is sustainable movement that works with your brain, not against it