Ever blurted something out and immediately regretted it? Or made a quick decision that felt right in the moment—but turned out to be a disaster? If so, you’ve experienced a moment of impaired response inhibition—a core executive function that helps us pause before we act.

For neurodivergent adults, especially those with ADHD or autism, this “pause” doesn’t always happen naturally. The result? Impulsivity in speech, choices, spending, social interactions, or even emotional outbursts. This article explores why that happens and how to build in practical strategies to help yourself—or the young people you support—develop stronger pause-and-plan habits.

What Is Response Inhibition?

Response inhibition is your brain’s internal braking system. It helps you:

- Stop and think before speaking

- Resist immediate temptations

- Choose a thoughtful response over a reactive one

For neurotypical brains, this often happens seamlessly. But for those with ADHD or executive function challenges, that “brake” is often slow or inconsistent.

Example: You know it’s not the best time to interrupt a meeting—but the thought feels so urgent that it bursts out anyway.

Why Is Response Inhibition So Hard?

Neurodivergent individuals, particularly those with ADHD, often have:

- A low threshold for boredom or discomfort

- High sensitivity to rewards (or immediate feedback)

- A nervous system wired for speed rather than pause

This means the brain is constantly chasing stimulation or relief. Add in poor working memory or time-blindness, and the ability to evaluate consequences gets bypassed entirely.

Signs of Poor Response Inhibition

You (or someone you support) might struggle with response inhibition if you notice:

- Blurting out thoughts or feelings before thinking them through

- Interrupting others often—even when trying not to

- Difficulty delaying gratification (e.g. spending, eating, reacting)

- Trouble managing anger or emotional outbursts

- Taking risks that seem impulsive or out of character

These behaviours are often misinterpreted as rudeness, carelessness, or defiance—but they’re usually neurological, not moral.

Building Better Pause-and-Plan Habits

Here are strategies that can help:

1. Name the Pattern

Awareness is the first step. Help clients (or yourself) notice when impulsivity shows up:

- “I noticed I interrupted again during our call.”

- “I spent money I didn’t plan to spend—again.”

2. Build in a Pause Mechanism

Simple physical or visual cues can be surprisingly effective:

- Use a breath or count-to-3 rule before responding

- Place sticky notes with prompts like “Think First” or “Is This Helpful?”

- Practice non-verbal self-checks (e.g. touching a bracelet as a reminder)

3. Create a Decision Checklist

For recurring impulse struggles (like spending or blurting), write down:

- What am I about to do?

- Why do I want to do it?

- What will the consequence be in 5 minutes? 5 hours? 5 days?

4. Use a Coaching Buddy

Whether it’s a therapist, coach, or trusted peer, external accountability strengthens internal regulation. Talk through scenarios beforehand, and debrief when things don’t go as planned.

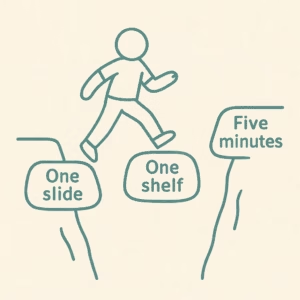

5. Practice Delay in Safe Ways

Start small. If someone often interrupts, encourage them to count to 3 before speaking. Gradually stretch that pause over time. Practice helps rewire the brain for delay tolerance.

For Parents and Educators: Responding With Curiosity, Not Punishment

Children and teens who struggle with response inhibition aren’t doing it to you—they’re navigating a system that doesn’t pause easily. Avoid labels like “rude” or “disruptive.” Instead, use:

- Gentle reminders: “Let’s pause and try again.”

- Emotion coaching: “I can see you wanted to speak—let’s find a better moment.”

- Previews: “This activity will need lots of patience. How can we plan ahead?”

Final Thoughts

Improving response inhibition is not about squashing spontaneity—it’s about gaining choice. For neurodivergent individuals, it means the power to pause, reflect, and choose a path forward that matches their values and goals. And like all executive functions, it’s a skill that can be coached, practiced, and celebrated.